To realize your dream, China,

Xi Jinping

wants to unite the country’s dozens of ethnic groups into a single national identity.

The programme of aggressive cultural assimilation – or ethnic amalgamation, as it is called in government documents and speeches – has been pushed to its limits in the northwest region of Xinjiang, where the largest mass raid by a minority group since World War II took place. The campaign started with expansion and intensification in other ethnically diverse areas.

In Inner Mongolia, a plan to expand education in the Mandarin language and use national textbooks instead of local versions has led to protests and a school boycott among students and parents who fear that the Mongolian language is threatened with extinction.

Part of the assimilation campaign is based on the security infrastructure set up to monitor and control the population. This includes the use of high-tech police surveillance in areas with large minority populations, a strategy used in Xinjiang to continuously monitor Turkish Muslims. The local government explained that this was necessary to ensure security in the area.

These practices have now spread eastwards to quiet areas such as Guangxi in southwestern China, where the largest minority group, the Zhuang, lives. The Zhuang profess animistic beliefs and have experienced few ethnic conflicts in the recent past.

In an already tightly controlled Tibet, the local authorities have launched a new military style vocational training programme for Tibetans in rural areas and have issued new rules to strengthen ethnic unity and patriotism in the region. Unpublished government documents show that the Chinese security forces are trying to install sophisticated monitoring and forecasting systems that can predict the activities of those involved.

The United Front Office, the organization of the Communist Party responsible for ethnic politics, has not responded to a request for comment.

There are 55 officially recognized ethnic minorities in China, and for decades the ruling Communist Party believed they would gradually integrate into the country’s dominant Han culture.

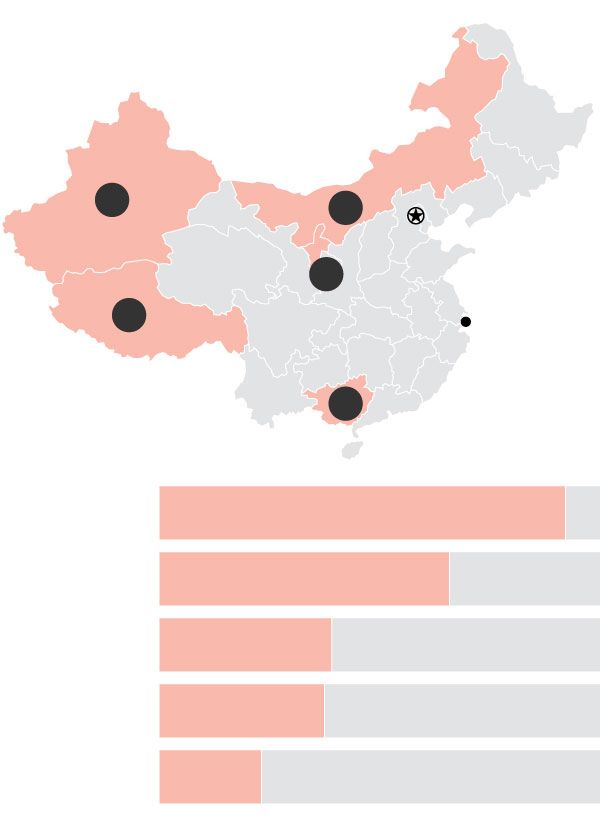

In regions

The Chinese government is stepping up its efforts to assimilate minorities in the autonomous regions.

Share of ethnic minorities

Under Mr. Xi’s leadership, the party’s patience has been exhausted. As the country’s strongest leader for decades, Xi wants to make China a dominant economic and technological power on an equal footing with the great dynasties of the past. His nationalistic Chinese dream is based on the idea that the country’s 1.4 billion inhabitants have a common identity.

Forming the collective consciousness of the Chinese nation is essential for realizing the Chinese dream of a great renaissance of the Chinese nation, Xi said at a government conference on ethnic politics last year.

China is already one of the most homogenous countries in the world, with the Han Chinese making up more than 90% of the population. It is also home to millions of traditionally nomadic Tibetans and Mongols, Turkish Muslims, groups with cultural ties to Southeast Asia and others, each with their own language, beliefs and customs.

Some of China’s largest minorities – and those who are culturally furthest away from the Han Chinese – live on the periphery of the country, in resource-rich border areas that are historically beyond the control of the Han Chinese. Just as he had taken a firmer stance in Hong Kong, Mr Xi took the view that control over ethnic minorities in China was essential to strengthen the territorial integrity of the country.

Major minorities

Although the 55 minority groups in China represent less than 10 percent of the population, some of them are the same size as in other countries.

China’s largest minorities, 2010*

Population of the country or territory, 2019.

China’s largest minorities, 2010*

Population of the country or territory, 2019.

China’s largest minorities, 2010*

Population of the country or territory, 2019.

Country or area, 2019

China’s largest minorities, 2010*

Earlier this month, Xi replaced an ethnic Mongolian at the head of the ethnic agency of the government with a Han Chinese civil servant. For the first time in more than half a century, a person with a minority background was appointed to lead the agency.

Under Xi Jinping, the Chinese dream is one of Han-centric cultural nationalism, said James Leibold, professor of Chinese ethnic politics at La Trobe University in Australia. The Chinese leadership believes that the party should be involved in creating this stability and national identity.

Autonomy versus assimilation

China chose a different approach within the Leninist system, which in

Mao Zedong

in 1949, when it was felt that ethnic minorities needed extra space and support before they could overcome their economic backwardness and join the proletarian revolution.

Although the Communist Party has always maintained ultimate control, Mao has created a system of autonomous regions, prefectures and provinces that has given minorities important positions in local government. Many have benefited from public investment. Members of minority groups were also exempt from China’s one-child policy and had received extra points for entrance exams to the country’s universities.

Poster from the 1950s with children from ethnic Chinese minorities in a classroom for a photo of Mao Zedong and Joseph Stalin.

Photo:

Michael Nicholson/Corbis/Getty Images

Between 2008 and 2009, when violent ethnic unrest broke out in the capitals of Tibet and Xinjiang, public opinion spoke out against the system. This has led to debates on the fairness of minority preference policies, with more and more Han Chinese treating Tibetans and Xinjiang Uighurs as ungrateful.

A renowned Chinese economist, Hu Anggang, and an anti-terrorist researcher, Hu Lianhe, channeled these frustrations into lobbying for second-generation policies that would actively eliminate ethnic differences.

The two Hassas, who are not parents, were inspired by the American idea of the melting pot, which they believe has contributed to maintaining national unity, developmental capacity and social order in the United States by minimizing cultural differences and creating a common identity. Referring to the collapse of the Soviet Union, they make the rapprochement of ethnic groups a matter of national security.

Others argued that the government should instead focus on combating discrimination, police repression and economic exploitation, which in their view fuel ethnic hostility.

Initially Mr Xi was discreet in the debate, at least in public, but it became stronger after the deadly terrorist attacks in Beijing and the southwestern city of Kunming in 2014, which were attributed by the police to the Uighur separatists in Xinjiang.

At a government conference on ethnic issues after the Kunming attack, Xi rejected calls to end the Chinese system of autonomous minority areas, enshrined in the Chinese constitution, but doubled calls for the formation of ethnic groups.

The participants of the meeting decided to bury the seed of love for the Chinese people deep in the heart of every child.

In a written answer to the questions, Tsinghua University economist Hu Angang said that China’s policy towards ethnic minorities and ethnic regions has been the most successful compared to other countries.

Hu Lianhe didn’t answer questions from the United Front Labor Department, his employer.

Distribution elsewhere

The change in policy has transformed Xinjiang. Since the end of 2016, in an unprecedented attempt to monitor and control the Turkish Muslim population in the region, the authorities have built thousands of new police stations, installed billions of dollars in advanced surveillance technology, destroyed religious sites and set up a regional network of detention camps.

Mr. Xi defended himself against criticism of the party’s approach in Xinjiang and said Beijing’s strategy in the region was correct at a conference in September.

Surveillance cameras on a street in Acto, Xinjiang region, China, in 2019.

Photo:

greg baker/Ageneration France-Presse/Getty Images

One element of this approach is now being replicated elsewhere: small, convenient police stations providing public facilities, such as wireless internet and emergency medical services, while at the same time serving as collection points for surveillance data and rapid response to security threats. These areas have not been identified as ethnic minority areas, although areas with a large minority population have some of the highest adoption rates.

In Nanning, the capital of the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region in southeastern China, in 2019 the authorities set up more than two dozen police stations and gas stations connected to the city’s digital security management system, such as their counterparts in Xinjiang, according to the local police, who call the stations anti-terrorist groynes.

The city of Golmud in Qinghai province, located on the Tibetan plateau, where ethnic minorities make up more than 30 percent of the population, created 13 community police stations in 2019, described by the local police as an innovative boost to its ability to ensure social stability and harmony.

SHARE YOUR IDEAS

What do you think the long-term impact of Chinese cultural assimilation programmes will be in their country and in the world? Take part in the discussion below.

In Gansu province in northwest China, home to some 13 million Muslims Hui, the capital city of Lanzhou has transformed police stations into a network of convenient stations housing the battle teams of the city’s tactical police unit, a special counter-terrorism unit, according to the Communist Party’s local law enforcement commission. Small police stations build a big world, says a May article online.

In recent years, none of the three cities has experienced terrorist attacks or serious ethnic violence.

The governments of Nanning, Golmud and Lanzhou have not responded to requests for comments.

There are indications that the Communist Party’s ethnic collapse campaign in Tibet is intensifying.

Since the beginning of the year, more than half a million rural and nomadic Tibetans have participated in vocational training programmes to improve their Mandarin and combat backwardness, according to a study by Adrian Zenz, an academic and critic of Chinese ethnic politics. The program, which provides newly trained workers throughout the region, has an alarming number of similarities with Xinjiang’s policy, Zenz wrote in a September report based on public Chinese government documents.

In January, the local Tibetan government passed a law to make the Autonomous Region a model area for ethnic unity and progress, weaving an ethnic mix into the fabric of Tibetan life, including religious teachings and activities.

A woman poses for photographers in front of a monument to Chinese leaders in Lhasa, Tibet Autonomous Region, on the 15th. October.

Photo:

Roman pilipei/Schutterstock

Public procurement documents released in November show that the Tibet Public Security Bureau has been working with Xinjiang security forces to carry out a new phase of criminal surveillance and investigation, fuelled by Beijing-based technology company Founder International Co. Details in the public version of the Tibetan contract were scarce, but the contracts the founder signed with other local police departments to install the same system describe his ability to create portraits of life goals and social circles through data including bank accounts, social media and mobile phones.

The founder did not respond to a request for comments.

Supply documents released the same month show that the Tibetan police have attempted to set up a database of persons of interest as part of a nationwide campaign to eradicate the evil that human rights activists claim has been used to deal with dissidents in the region. According to the documents, authorities want to link the database to a predictive surveillance system that can predict the criminal activity of gangsters and the forces of evil through various fine-grained graphical reports, while providing unique data for hack attacks and law enforcement.

The Tibetan Government has not responded to a request for comments.

New generation

The Chinese authorities are always alert to the appearance of diversity, even at major political gatherings where the state media ceremoniously dress up representatives of minorities. But this tolerance of cultural differences is superficial, says Dilnur Reihan, an Uyghur sociologist at the National Institute of Eastern Languages and Civilizations in Paris.

By combining assimilation and appropriation led by Mr. Xi, China is creating a new form of colonial identity, she said.

In some cases, forced assimilation efforts have made Mr Le C a rarity.

The authorities in the tropical island province of Hainan caused outrage in September when they banned young Utsul women, a local Muslim ethnic group with a population of about 10,000, from wearing headgear to school. The government changed course after the public anger and the class boycott, according to several Utsuls. According to them, the construction of a large mosque, financed by donations from the community, was halted for months because of its dome and other non-Chinese architectural features.

An old mosque in the village of Fenghuang, on the southern island of Hainan, China. A new mosque in the neighborhood was shut down because people were worried about the non-Chinese design.

Photo:

Jonathan Cheng/ Wall Street Journal

In August, the local government of Inner Mongolia announced a plan to promote Mandarin education and include it in national textbooks. Thousands of students in the region boycotted classes and took to the streets, according to locals and Mongolian human rights activists.

The governments of Inner Mongolia and Hainan have not responded to a request for comments.

In Tongliao, a large Mongolian city with more than three million inhabitants in eastern Inner Mongolia, the inhabitants said that the new education policy had been implemented despite the opposition.

The young mother said that the Mongols in the city were still angry about the change, but felt powerless. It’s government policy, she says. How can we fight this?

people demonstrated on 15 September in Ulaanbaatar, neighboring Mongolia, against China’s plans to expand Mandarin language education in Inner Mongolia.

Photo:

bambasuren bamba shiren/agency France-Presse/Getty Images

-Chun Han Wong has contributed to this article.

Write to Eva Xiao at [email protected], Jonathan Cheng at [email protected] and Lisa Lin at [email protected].

Copyright ©2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All rights reserved. 87990cbe856818d5eddac44c7b1cdeb8

Related Tags: